Happy Thanksgiving from our family to yours!

The Virginia Thanksgiving Festival 2017

The Virginia Thanksgiving Festival at Berkeley Plantation in Virginia. Click here to view more

Photo courtesy of Charles Wissinger

#TBT Sea Lion Ship

#TBT to 2010 at the Barcelona Harbor.

Veterans Day

Thank you to all who have served past and present & to all the veterans from Henricus Citie Militia & Henricus Historical Park #VeteransDay #SemperFi

#TBT Henricus & GWAR

Remember when Henricus Citie Militia & GWAR frontman Oderus Urungus were at CultureWorks Richmond?

Dennis Strawderman, Paul Carter & Patrick Blackburn caught up with GWAR fontman Oderus Urungus aka Dave Brockie at the CultureWorks Richmond 2013 Arts and Culture Xpo, while raising awareness for Henricus Historical Park, which apparently was quite popular and the most liked booth at the event!

The Sea Lion Project Update 02-17-2017

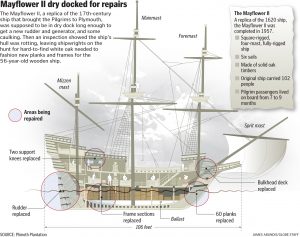

Wharf boring beetles, (Narcerdes melanura) have invaded the wood of the Mayflower II, according to an article in the Boston Herald, and much of the Plymouth-based ship’s hull suffers from rot. The popular tourist attraction, considered to be the star of the show at Plimoth Plantation, needs about 60 percent of the its planking replaced below the waterline, and was becoming unsafe for visitors.

According to Whit Perry, director of maritime preservation and operations at Plimoth Plantation: “She needs major structural frame repairs and planking. Without a project of this magnitude now, her days would be numbered — and that would be tragic,” for the replica built in Great Britain and sailed to the U.S. as a gift of friendship in 1957. In November 2016 the ship sailed to Mystic Seaport for a 7.5 million dollar refit estimated to take 2.5 years for completion.

One of the major problems in repairing replica ships is where to find the needed lumber? Repairs need to be made with white oak “air dried” for over three years, a commodity almost impossible to locate in large quantities in our modern age. Fortunately for the folks at Plimoth Plantation they were able to find a good stand of oak trees in Kentucky sufficient for their needs.

When the Sea Lion ship was sent to Scarano Boat Builders in Albany New York for repairs we had no idea just how hard 300 year old oak lumber was to come by. Scarano Boat Builders has earned an excellent reputation for building and restoring replica sailing ships of all sizes. However, several weeks ago we got a call from Albany saying they hadn’t been able to locate the lumber needed for the replacement deck beams and Sampson Posts for the Sea Lion. Nowadays, laminated timbers are often used for support beams due to the lack of availability of seasoned white oak.

But the Sea Lion was designed and built just like English ships were constructed 400 years ago long before laminated beams were first used in the mid nineteenth century. We offered to search for sources of white oak and after contacting lumber companies all across the east coast could find nothing in the needed size and quantity for the job other than green or reclaimed lumber.

Since green wood was not an option we explored the possibility of using reclaimed lumber and discovered it came with many drawbacks along with its high cost just as well. Reclaimed wood often shows signs of decades of use, contains mold and mildew, and is infected with termites and other wood-eating pests. Reclaimed wood often contains old nails, metal pegs, or even bullets, all hazardous objects when hit with a power saw.

Not willing to throw in the towel, I remembered a Virginia company renowned for building beautiful timber frame homes and commercial buildings. Several years earlier, Dreaming Creek, located nearby in Powhatan Virginia, had helped our militia group by providing the wood needed for two cannons we were building. Dreaming Creek built the The Blackfriars Playhouse in historic Staunton, Virginia, the world’s only re-creation of Shakespeare’s indoor theatre and the Marine Corps Semper Fidelis Memorial Chapel just to name two of their many accomplishments.

After searching through all their mills, Stuart Bailey, my contact at Dreaming Creek, was able to locate the needed lumber. Stuart gave Ron Blackburn, Sea Lion Foundation board member and master carpenter, and me a tour of his Powhatan plant where we were able to see the quality of the white oak we would be getting. The Sea Lion Foundation owes Stuart Bailey, and everyone at Dreaming Creek, a huge thanks for all their hard work in locating the lumber. The wood is already being cut to the sizes needed by Scarano Boat Builders and prepared for shipment to Albany.

Just as the Mayflower II has become loved by visitors to Plimoth Plantation we feel certain the Sea Lion will soon become the center of attention at Henricus Historical Park. While the journey is far from over, locating the proper lumber for the restoration project has moved us one giant-step closer to our goal.

– Dennis Strawderman, Founder of the Henricus Citie Militia.

New Season begins at Henricus Historical Park

Its time to clean your muskets and sharpen your swords

as anew season begins at Henricus Historical Park!

Visit www.henricus.org for more information on upcoming events.

The Mystery of the Copper Maximilian Armour

Having viewed a myriad of documentaries exploring lost treasures from throughout history including the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy Chalice, and the legendary Lost City of Gold I was hesitant about piling yet another mystery onto the heap. But since I am certain that any day now most of those afore mentioned treasures will be recovered from the Oak Island money pit I thought it safe to finally reveal the Mystery of the Copper Maximilian Armour.

Several years ago I chanced across an impressive suit of Maximilian armour for sale of unknown origin. The seller represented the suit as a well-executed Victorian replica largely because it was hammered out of copper instead of iron or steel. The workmanship on the armour is superb with closely spaced fluting on the cuirass, pauldrons, and other elements of the armor. Unlike more cheaply made replica armours the flutes are edged along both sides with a chiseled groove accentuating the beauty of the fluting. The cuirass is short-waisted and of globose form just like the originals. The helmet has a neck-guard composed of three articulated plates but is not nearly as appealing to the eye as the rest of the armour. Supposedly the armour was originally “tinned” to give it the appearance of steel, however I can find no evidence of tin plating anywhere on the surface even in hidden recesses where it wouldn’t have easily worn away. The copper is somewhat tarnished from age and I decided not to polish it since it might damage the surface or diminish the value of the suit. I had actually considered re-tinning or silver plating the surface to give it more of the appearance of an original armour.

Several years ago I chanced across an impressive suit of Maximilian armour for sale of unknown origin. The seller represented the suit as a well-executed Victorian replica largely because it was hammered out of copper instead of iron or steel. The workmanship on the armour is superb with closely spaced fluting on the cuirass, pauldrons, and other elements of the armor. Unlike more cheaply made replica armours the flutes are edged along both sides with a chiseled groove accentuating the beauty of the fluting. The cuirass is short-waisted and of globose form just like the originals. The helmet has a neck-guard composed of three articulated plates but is not nearly as appealing to the eye as the rest of the armour. Supposedly the armour was originally “tinned” to give it the appearance of steel, however I can find no evidence of tin plating anywhere on the surface even in hidden recesses where it wouldn’t have easily worn away. The copper is somewhat tarnished from age and I decided not to polish it since it might damage the surface or diminish the value of the suit. I had actually considered re-tinning or silver plating the surface to give it more of the appearance of an original armour.

After displaying the armour for a single event I carefully stored it away awaiting the time when space will hopefully become available to exhibit it on a more permanent basis. I hope to create a continuum of arms, armour, and museum quality model ships to visually demonstrate the many advances in these areas during the Great age of Discovery (1492 through the early 17th century and the establishment of Henricus). I have already obtained several original weapons (a matchlock musket and a wheellock carbine) and components of period armor for the display along with several ship models. Hopefully this dream will become a reality and augment the Sea Lion ship exhibit once it arrives at Henricus Historical Park.

It has baffled me somewhat since first obtaining the suit as to why anyone would have worked with copper instead of steel unless plating the surface with silver, gold, or some other medium was their intention. Recently, with the excitement of the holidays ebbing a bit, I decided to inspect the armour a bit more closely.

First off, I noticed evidence of earlier attachments for the gloves inside the mitten gauntlets as well as rivets of a more modern form present from place to place attaching replacement leather straps to the suit. There were signs of light pitting here and there as well, a somewhat perplexing observation since the suit was supposedly made of copper. Then, whilst manipulating the lames of one of the gauntlets, I noticed a shiny glow beneath the dull surface where one of the scalloped edges had worn away the copper.

Upon closer examination with a magnifying glass I realized the metal beneath was steel. I leapt up from my chair and ran to the refrigerator, which in my house is covered from top to bottom with magnets of all sorts from tourist haunts across the planet. Grabbing one of the magnets I returned to my work space and quickly discovered that the entire gauntlet was made of steel. Fighting my way through Christmas debris in the storage room to the boxed armor I tested the other elements of the suit and discovered they were steel underneath as well. No matter where I placed it the magnet clinked solidly against the metal and stuck fast. The original rivets appear to be steel as well, though they are too close to the rest of the surface to be absolutely certain. Why, the realization struck me, had I never thought of the possibility before? I had figured all along that the description provided by the seller, a well-respected dealer, was accurate, but in retrospect realized he was relying on an appraisal from another party just as well.

I was ecstatic, since I had always considered the armour to be merely decorative, no matter its age or beauty, since copper would never have turned a lance or crossbow bolt as well as steel. No self-respecting man-at arms would have chanced wearing such a suit other than on parade. A parade armour is not nearly as desirable for the purposes of our future display as an actual field armour.

Though it was New Year’s Eve I called a friend and renowned armourer, James Arlen Gillaspie, to discuss my discovery. James has handled some of the finest armor in the world and is an expert in the field. He answered on the forth ring and was almost as baffled as I was at why anyone would copperplate such a fine suit of armor. According to James it could have been done with the intention of gold or silver plating the suit. Or perhaps the copper plating was an effort to cover-up the damaged or pitted surface of an otherwise well-proportioned period armor. The rivets being steel as they appear, instead of a non-ferrous metal as common on Victorian replicas, would be added evidence that some components of the armour might have been made in an earlier age.

With several tall stacks of books on armour and weapons, as well as a plethora of catalogs from armor sales unable to give me an answer, I turned to the internet, but once again without any real success. Soon I’ll be packing up a few of the smaller items from the armour and shipping them off to James Gillaspie to hopefully get an answer from an expert. Until then I sit here in wonder, much like Geraldo Rivera poised before Al Capone’s secret vault, contemplating what truth lies behind the mystery of the copper Maximilian Armour.